Day #6:

The sixth day was my first day at the Cleveland Clinic shadowing Dr. Walter Cha, a general surgeon who mainly performs gastric bypasses, hernia (abdominal tear) closures, and cholecystectomies (gallbladder removals). The sixth day was similar to day four (blog #3) with Dr. Hoffer, where Dr. Cha introduced general surgery and visited patients.

I arrived at the Clinic's atrium around 7:30 AM. I met Dr. Walter Cha in his office and walked to a conference room. He explained the basics of his job as a general surgeon and asked me what my goals were for the week. He explained that today was his clinical day, meaning that, like on day four at UH, we would see patients in person. So, he opened the Epic (company) program on his computer and waited for a patient to arrive. First, his nurse practitioner called the patient from the waiting room, brought them to the weighing scale and height instrument, and took them to the room for initial questions. A green light on Dr. Cha's computer screen appeared once they finished, indicating that the patient was ready for the doctor. Dr. Cha and I walked to the patient's room, and he introduced himself and me to the patient. He started by asking specific questions about pain and past hospital visits. Then, Dr. Cha had the patient lie on a robotic chair that could raise and lower so that he could feel the abdomen for lesions or hernias. Once he finished his examination, he showed the patient their X-rays. Then, he either referred them to a more specialized doctor, ordered additional imaging, or outlined potential surgery. I left around noon because he said that I had the idea of his job's clinical aspect.

This is an example of an umbilical hernia. Part of the abdominal wall by the umbilical region (bellybutton) tears, allowing for the intestine to enter the space and cause pinching and blockages within the intestinal tract.

Day #7:

On the seventh day, Dr. Cha took me to the OR where he performed a gastric bypass.

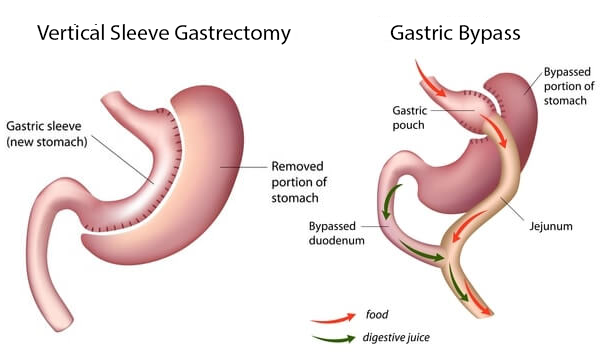

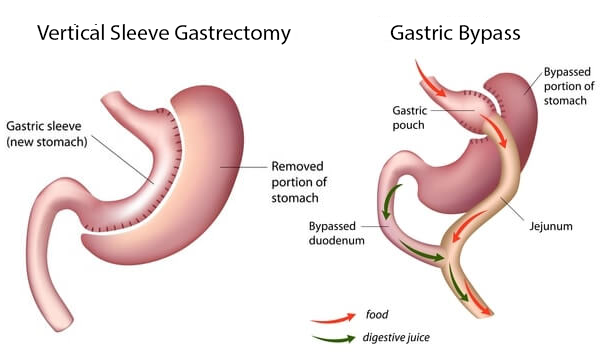

I met Dr. Cha in his office at 7 AM this morning in scrubs, and we walked to the OR. My initial impression (compared to UH) was that the Clinic's OR is much larger and has screens everywhere (it almost looked like the Arrival/Departure screens at the airport but with various OR surgeries). We visited the patient Dr. Cha was going to operate on in pre-op to check in with her and her family. About a minute later, her bed was wheeled through the OR and into the OR room. When Dr. Cha and I arrived (about 10 minutes later), she was already sedated and prepped for the surgery. The surgery I watched today was a gastric bypass or a bariatric surgery, where the stomach is shrunk and the jejunum becomes attached to the shrunken gastric pouch, bypassing the duodenum and pyloric sphincter. The uses of both the duodenum and separated stomach are only to provide digestive juices like HCl (hydrochloric acid) and pepsin, the enzyme that breaks down proteins in the stomach, to the shrunken pouch and jejunum. In essence, the surgery aims to induce a regulated state of malnutrition in the patient, allowing them to lose weight (Less chance of absorption = less fat in the body). The unique thing about this procedure was that Dr. Cha and his assistant used a robot to perform laparoscopically. There are many benefits of using a robot. First, large hand movements translate to smaller robot arm movements, meaning any minor tremor in the surgeon's hand is minimized or eliminated. Second, the surgeon can use four tools at the same time, which increases efficiency. Third, it's pretty cool to watch. So, to start the procedure, a surgeon cut 4 or 5 ports (small, round holes lined with plastic) into the patient's abdomen above the stomach and small intestine. They also injected gas into the abdomen to increase the workable space. Something interesting I learned was that the patient is on a strict diet of no carbs or sugar for two weeks before the procedure. When you eat carbs (which essentially turn into sugar in the body) or sugar, the body stores the excess inside the liver. When you stop eating both products altogether, the size of the liver shrinks significantly, contributing to even more usable space inside the abdominal cavity during the procedure. Another doctor moved the robot above the patient, connected each robotic arm to different ports, and installed removable tools like staple guns, tissue melters, and clamps (they looked similar to tongs). Then, the surgeons put their heads into an expensive VR headset-looking device and started the procedure by controlling the robotic arms with various metal instruments. They did their surgeon thing for about an hour and a half until the medical jargon I mentioned above was completed. The patient is then woken up and sent off to postoperative care. The next procedure on the list was a cholecystectomy, but I was also scheduled to observe one next Monday, so I ended my day there.

Here is a smaller version of a similar robot used in the procedure. In the photo above, the robot's arms are positioned on the test dummy's abdomen and are attached through various ports. In the back, the surgeon is peering though a device that sees directly inside the patient in 3D while they use their hands and feet to control each arm. The robot used on day seven needed two surgeons to operate.

Day 8:

My eight day was similar to day six, where Dr. Cha and I visited patients. The difference between both days was that day six consisted of more hernia patients and day seven was mainly bariatric/sleeve patients.

At around 8:30, I walked up to Dr. Cha's office, and he showed me his computer screen with all the patients. Once a patient arrived and the nurse practitioner saw them, Dr. Cha and I walked into their room, and he started asking pointed questions. Compared to day six (another clinical day at CCF), today's cases were more related to gastric bypass or bariatric surgery. Most of the patients we saw were overweight (had a BMI of ~50; normal is 18.5 - 24.9). The most common question they asked was whether they would be a better candidate for a gastric bypass or a gastric sleeve. A gastric sleeve is when the surgeon only removes the pouchy part of the stomach without touching the intestinal tract. Because the stomach is about 80% smaller after the procedure, the containment creates a higher pressure environment, which increases the chance for gastric juices to enter the esophagus from the cardiac sphincter, causing heartburn. So for patients with GERD (acid reflux), a bariatric procedure would be better to reduce or eliminate GERD symptoms because the gastric juices don't come in contact with the esophagus anymore post-operation. Another consideration is the patient's overall health. Because a gastric bypass is a riskier procedure, if a patient's vitals (cholesterol, sugars, BP, psychological state, etc.) aren't stable, the operation becomes even more risky. Therefore, a sleeve would become the better option. Also, a sleeve would be best if a patient is deficient in certain minerals like iron and calcium because the surgeon removes a large part of the intestine that absorbs nutrients like iron and calcium in a gastric bypass. Whereas after a sleeve, the patient can still absorb the nutrients through their intestinal tract and wouldn't need occasional blood transfusions to supplement the lacking nutrients. That said, most of his patients went with bariatric surgery. In contrast, a few–the ones with GERD, nutrient deficiencies, or notably bad health conditions–chose sleeves. After around 10 patients, Dr. Cha said goodbye, and I left the hospital.

Here is a good diagram of both procedures.

Comments

Post a Comment