Day #1:

Today I arrived at the UH Bolwell building at 7:30 and signed in through the volunteer kiosk. I met Dr. Hoffer in the neurology lobby and walked to his office together. He explained what his job was generally about and asked about my goals for the week. He explained that a significant OR (operating room) case was canceled that day because of some insurance mess-up. Still, he had already postponed his other patients until a different date. So, he brought me to the neuro ICU (intensive care unit), where I met some doctors/fellows/other shadows. We started in a small room with about ten different doctors. A lead doctor arrived and asked for a one to two-sentence overview of each patient (there were ~10 in total) accommodated by imaging. After that, we all went from room to room, checking patients’ status. The patient in the worst condition had bloody, coagulated stools and needed an endoscopy to check for stomach ulcers. They found one, but it wasn’t the cause of the bleeding. They handed me a paper with information on each patient, but I couldn’t understand the medicinal jargon. When the round finished, Dr. Hoffer and I returned to his office around noon and waited for a 12:30 patient. While we waited, he showed me some YouTube videos on stroke disorders like aphasia, anosognosia, and left neglect. Unfortunately, his patient didn’t show up. So, he let me go home early, at around 1:10 PM.

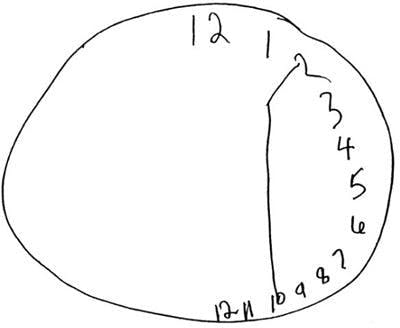

The photo on the left is an empty ICU room and the photo on the right is a famous example of a left neglect test, where a recovering stroke patient is tasked to fill in a clock. As you can see in the photo, the patient lacks awareness of anything to the left; it doesn't exist to them. Another example is when a patient eats a plate of food, but leaves the left side untouched.

Day #2:

I spent day #2 in the operating room (OR), observing two unique cases: a ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement and a brain tumor removal.

Today I arrived at the hospital at 7:00 for early preparation for surgery. I went to floor two, where I met Dr. Hoffer, who let me into the neurosurgery OR wing. I received scrubs, a surgical mask (like a standard surgical mask, but with four straps tied above and behind the head), and a surgical cap. We went to OR 23, where I set down my bag and began preparing for the first surgery of the day: A ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. The procedure is done to treat hydrocephalus (meaning: water in the brain). Hydrocephalus can occur when too much spinal fluid builds up inside the brain's ventricles. A shunt (valve) is placed to help drain excess fluid to prevent the pressure inside the brain from getting too high. To start the procedure, Dr. Hoffer drilled two holes, one in the skull and one in the abdomen. He stuck a probe into the brain until a stream of spinal fluid squirted out. Then, he followed the probe with a small tube and let the tube hang out of the brain. His assistant used a larger probe and released the skin from under the skull. Hoffer stuck a larger tube from the hole in the abdomen and shoved it within the body until it reached the neck. He then pulled the larger tube from the skull until it hung out of the head like the smaller tube. The two tubes were connected via a ball valve that let spinal fluid flow when the patient lies down. The incision into the skull and abdomen was then sutured and sanitized, and the patient was sent to post-op recovery. In total, the procedure took about an hour. My second surgery was in OR 25: removing a brain tumor. The process of removing the cancer didn’t initially seem too complex. They use a 3D mapping thing that uses shiny balls to align the patient’s head to an X-ray. It looks like one of those CGI costumes they use in the movies. To start, the surgeon made an incision into the skin above the tumor. Then, he used a drill/saw-looking device to cut through the bone and expose the brain. Once the brain was exposed to the environment, the anesthesiologist woke up the patient. They use electrical probes on the patient’s brain to test for where they can or can’t send electricity (called motor language mapping). If done improperly, the patient couldn’t speak again after the procedure. The neurologist sent different electrical frequencies through the exposed brain while the patient groggily counted to twenty until they couldn't talk due to a response from a specific frequency. From there, the anesthesiologist administered the second dose of sleepy meds via IV. Unfortunately, this patient could not be put to sleep again, so the neurosurgeons had to remove the tumor while the patient was awake. The nurses distracted the patient with friendly questions for the duration of the procedure. To remove the cancer, the surgeons made an incision in a brain groove and dug slowly into the tissue, periodically checking their progress with an ultrasound machine. Once they found the tumor, they removed it with tweezers and a spoon, which looked like a miniature ice cream scooper. After everything was gone and cleaned with a cold saline solution, the hole in the brain was closed with the previously removed skull bone and meticulously sutured back to the skin. The patient was then taken to post-op recovery. In total, the procedure took roughly 3.5 hours. I met up with Dr. Hoffer, finishing his procedure in the adjacent room, and we walked out together.

You description of the brain surgery performed of an awake patient is utterly terrifying! The fact that you are capable of calmly watching it and recount all the details, tells me that you may have what it takes to become a doctor. Sounds like you are learning a lot about the profession!

ReplyDelete