Day #3:

My third day shadowing Dr. Hoffer at UH was similar to the second day, but instead of two short surgeries, I observed a longer one.

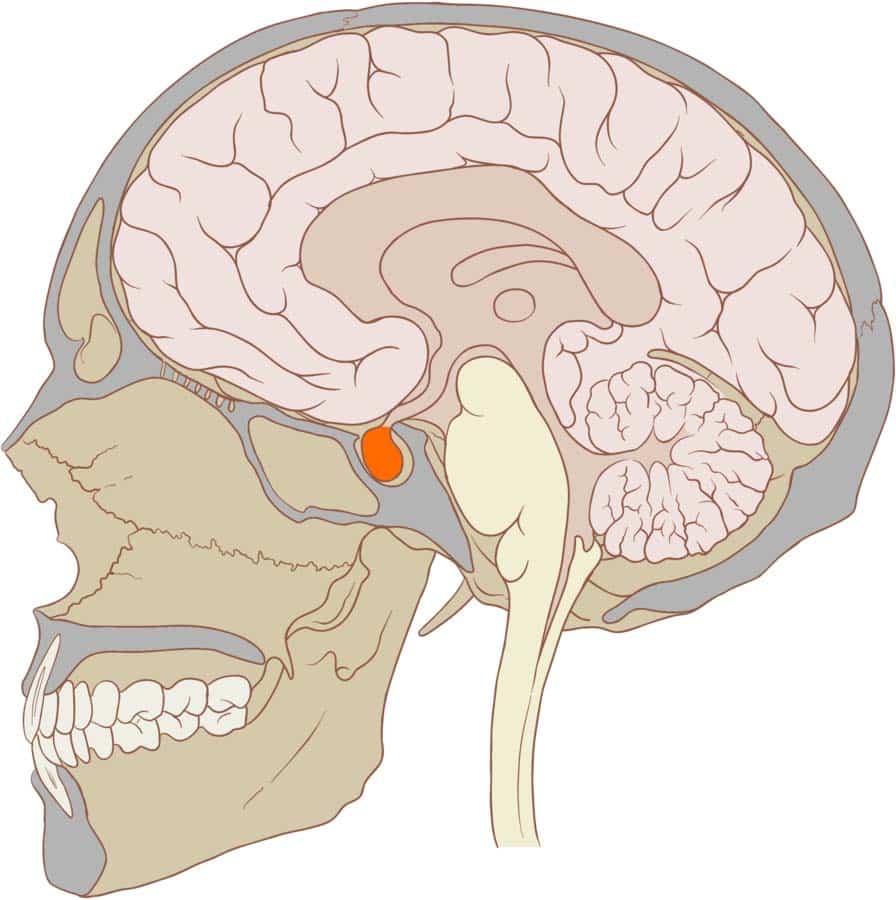

I met Dr. Hoffer again at 7:00 AM, and we walked to the changing room to change into scrubs. The first procedure I went to in OR 26 was interesting: removing a tumor around the pituitary gland. The ENT surgeon stuck a few metal rods up the patient's nose to accomplish this task. One of the rods had a camera (to be honest, I expected better resolution from a machine that probably costs more than a nice-sized house), which connected to a large screen. The second rod had various tools, like a plier, a grinder (which looked like a miniature disco ball), and a knife. In unison, the tools, visualized by the camera, cut through each sinus wall until they reached the sphenoid bone in the skull. Then, they used a sharp plier to open the bone and pop the tumor sack, releasing the pressurized greenish-yellow tumor from the pituitary gland. After the area was cleaned using a saline solution, the hole in the sphenoid was patched, and the patient was sent on their way to post-op recovery. In total, the procedure took about 5 hours. I met up with Dr. Hoffer in OR 24 for another surgery about to start, but he told me he was leaving. So, we both walked out together.

The photo on the left shows the pituitary gland in red. The photo on the right is what the procedure looked like inside the OR. The screen behind the surgeons is a live-feed from the camera inside the patient's nasal cavity.

Day #4:

For my fourth day, Dr. Hoffer visited patients referred to him by primary care doctors and other neurologists. I'm glad that I spent a day observing the clinical side of neurosurgery because it opened my eyes to the doctor's day-to-day of visiting patients.

Today, I woke up at 8 AM to go to UH’s Green Road campus. I met Dr. Hoffer and his assistant nurse, Jim, in their office in the neurology department. Dr. Hoffer pointed to his screen and showed me the 10 or so patients for the day, three of whom were virtual. To start the process of visiting a patient, a green light indicator appears on the UH doctor’s program relaying that the patient is present and has signed in. Jim walks the patient to the room, where he asks basic questions regarding areas of pain and past medical history. Once he finishes, he walks back to the office, where he overviews the patient to Dr. Hoffer, while he views any X-rays of the brain and spine. Then, Dr. Hoffer and I walk to the patient’s room. He asks a bunch of specific questions. Only about 10% of the patients we met needed surgery. What was interesting to me was how people would respond to being told they didn’t need surgery. Some people were relieved, while others would start making up symptoms that they believed would require surgery because they "tried everything else" and, to them, surgery was the only method left. Overall, it was an eye-opening day exploring the behind-the-scenes of a doctor's visit.

Day #5:

For my fifth and last day at UH, I was originally planned to spectate the angio suite where they capture the blood vessels in the brain, but not much was happening in the suite, so I spent another day in the OR to spectate a shorter procedure.

I arrived at the neurosurgery OR at 7 AM to meet Dr. Hoffer. We walked to the changing room and changed into scrubs and put on surgical masks and head coverings. The first case was in OR 24: a shunt placement into the jugular vein (the main vein from the brain leading to the superior vena cava). The patient had a stomach infection, which infected and blocked the previous shunt positioned in the abdomen. So to prevent the infection from reaching the brain, the shunt from the abdomen needed to be removed and repositioned into the jugular vein, which leads directly to the heart. To start the procedure, one of the resident surgeons located the vein using an ultrasound (U/S) machine. On the U/S screen, there were two large circles: the jugular vein and the carotid artery. To figure out which is what, he pressed on the patient’s neck. Because the artery has a much higher pressure than the vein, it kept its shape and pulsated with the heart’s beating, whereas the vein compressed. He marked the position of the vein using a sterile pen. Then, Dr. Hoffer made an incision into the brain and stuck a catheter into a fold until spinal fluid started dripping out of the needle’s tip. He connected the catheter to a one-way valve (the shunt). Both the resident surgeon and Dr. Hoffer made a small incision into the jugular vein. Once the vein was open, they pushed a small plastic tube through the opening until it reached the right atrium of the heart (confirmed with an X-ray). Given that X-rays release a lot of radiation, everyone in the room was given lead vests to wear. The valve was then connected to the tube allowing for the flow of spinal fluid to reach the heart. Both incisions were sanitized and closed with sutures, and the patient was led to postoperative recovery. In total, the procedure took about 30 minutes. Since it was Dr. Hoffer’s only procedure for the day, I left the hospital, concluding my time shadowing him at UH.

Comments

Post a Comment